Exact Inference in Bayesian Networks: A Complete Guide (updated 2026)

Introduction

Imagine you’re building a medical diagnosis system that needs to determine the probability of a disease given various symptoms. Or perhaps you’re developing a recommendation engine that must reason about user preferences under uncertainty. These scenarios demand more than simple calculations—they require sophisticated probabilistic reasoning over complex dependencies. This is where exact inference in Bayesian networks becomes indispensable.

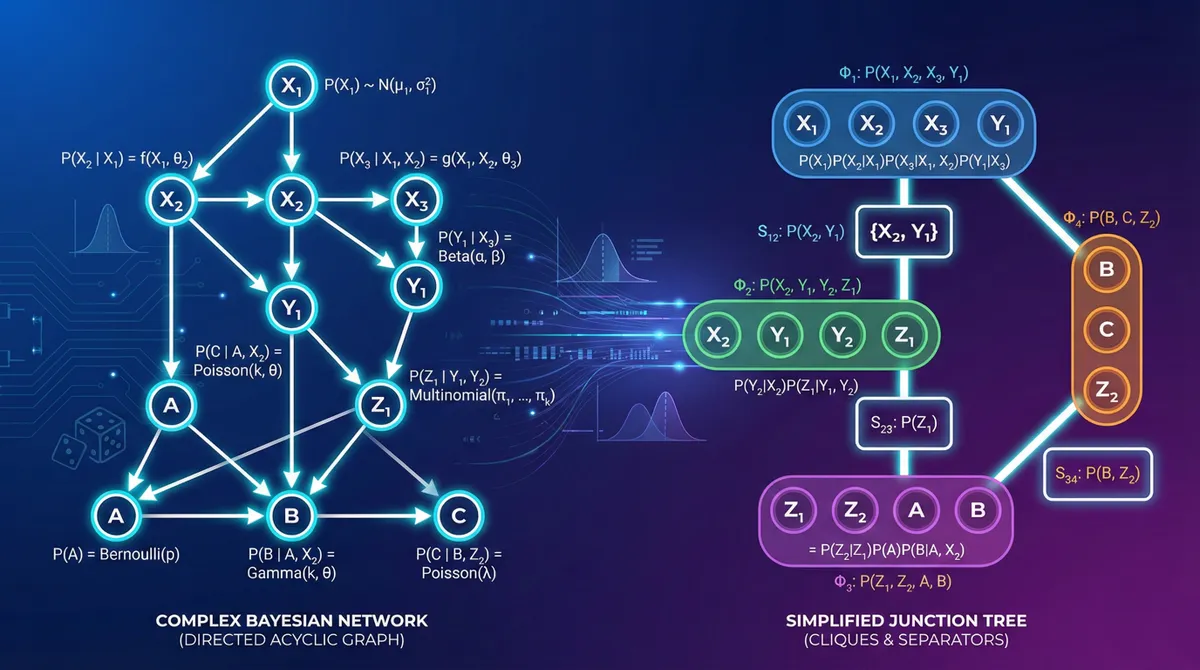

Bayesian networks are powerful probabilistic graphical models that represent conditional dependencies between variables through directed acyclic graphs (DAGs). While building these networks is straightforward, the real challenge—and power—lies in performing inference: computing probability distributions for query variables given observed evidence. This article explores exact inference methods that guarantee mathematically precise results, as opposed to approximate methods that trade accuracy for computational efficiency.

You’ll learn the fundamental algorithms (variable elimination and junction tree), understand their computational complexity, implement them in Python using pgmpy, and recognize when exact inference is feasible versus when you need approximation methods. We assume basic familiarity with probability theory and Python programming.

Prerequisites

Before diving into inference algorithms, ensure you have:

- Mathematical Foundation: Understanding of probability theory (conditional probability, Bayes’ theorem, marginalization)

- Python Environment: Python 3.10+ with the following packages:

pgmpy>=1.0.0(for Bayesian network operations)numpy>=1.24.0(for numerical computations)pandas>=2.0.0(for data manipulation)

- Graph Theory Basics: Familiarity with directed acyclic graphs (DAGs), nodes, and edges

- Optional: Understanding of complexity theory (Big-O notation) for performance analysis

Install required packages:

pip install pgmpy numpy pandas --break-system-packagesUnderstanding Bayesian Networks

A Bayesian network represents a joint probability distribution over a set of random variables through a DAG where:

- Nodes represent random variables

- Directed edges encode conditional dependencies

- Each node has a Conditional Probability Distribution (CPD) that quantifies effects from parent nodes

The key advantage of Bayesian networks is their compact representation. Instead of storing an exponentially large joint probability table, we factor the distribution using conditional independence:

$$P(X_1, X_2, …, X_n) = \prod_{i=1}^{n} P(X_i | \text{parents}(X_i))$$

This factorization dramatically reduces the number of parameters needed. For example, with 10 binary variables, a full joint distribution requires $2^{10} - 1 = 1023$ parameters, while a well-structured Bayesian network might need only 30-40 parameters.

In this classic example, WetGrass depends on both Sprinkler and Rain, which are conditionally independent given Cloudy. This structure allows efficient reasoning about causes and effects.

What is Exact Inference?

Exact inference computes probability distributions with mathematical precision (subject only to floating-point rounding errors). The primary inference tasks include:

- Marginal Inference: Computing $P(X)$ by summing out all other variables

- Conditional Inference: Computing $P(X|E=e)$ where $E$ represents evidence variables

- Maximum a Posteriori (MAP): Finding the most likely assignment $\arg\max_X P(X|E=e)$

The fundamental challenge is computational complexity. Cooper proved in 1990 that exact inference in Bayesian networks is NP-hard in the general case. However, for many practical networks with favorable structures (low tree-width), exact inference remains tractable and is the preferred method for its guaranteed accuracy.

Variable Elimination Algorithm

Variable elimination is the foundational exact inference method. The core insight is to exploit the distributive law to avoid redundant computation by eliminating variables one at a time in a strategic order.

How Variable Elimination Works

The algorithm systematically removes (eliminates) non-query, non-evidence variables by:

- Collecting factors involving the variable

- Multiplying those factors together

- Marginalizing (summing out) the variable

- Storing the resulting factor for subsequent operations

Consider computing $P(D|E=e)$ in a network. The naive approach computes the full joint distribution and sums over all non-query variables—requiring exponential operations. Variable elimination rearranges these summations to minimize computation.

Mathematical Foundation:

For a query $P(X|E=e)$, we need:

$$P(X|E=e) = \alpha \sum_Z P(X, Z, E=e)$$

where $Z$ represents hidden variables and $\alpha$ is a normalization constant. Using the network’s factorization:

$$P(X|E=e) = \alpha \sum_Z \prod_i \phi_i$$

where $\phi_i$ are factors (CPDs). Variable elimination strategically orders summations to create intermediate factors efficiently.

Implementation Example

Let’s implement variable elimination using pgmpy on a medical diagnosis network:

import numpy as np

from pgmpy.models import DiscreteBayesianNetwork

from pgmpy.factors.discrete import TabularCPD

from pgmpy.inference import VariableElimination

# Define network structure: Smoking -> Cancer -> X-ray

model = DiscreteBayesianNetwork([('Smoking', 'Cancer'),

('Cancer', 'XRay')])

# Define CPDs with realistic medical probabilities

# P(Smoking)

cpd_smoking = TabularCPD(

variable='Smoking',

variable_card=2,

values=[[0.7], # Non-smoker

[0.3]] # Smoker

)

# P(Cancer | Smoking)

cpd_cancer = TabularCPD(

variable='Cancer',

variable_card=2,

values=[[0.98, 0.75], # No cancer

[0.02, 0.25]], # Has cancer

evidence=['Smoking'],

evidence_card=[2]

)

# P(XRay | Cancer)

cpd_xray = TabularCPD(

variable='XRay',

variable_card=2,

values=[[0.95, 0.20], # Negative X-ray

[0.05, 0.80]], # Positive X-ray

evidence=['Cancer'],

evidence_card=[2]

)

# Add CPDs to model

model.add_cpds(cpd_smoking, cpd_cancer, cpd_xray)

# Verify model consistency

assert model.check_model()

# Perform inference

inference = VariableElimination(model)

# Query: What's the probability of cancer given positive X-ray?

result = inference.query(

variables=['Cancer'],

evidence={'XRay': 1} # 1 = Positive X-ray

)

print("P(Cancer | XRay=Positive):")

print(result)

# Output interpretation:

# This shows posterior probability of cancer given positive X-ray

# Should show significantly increased cancer probabilityComplexity and Elimination Ordering

The computational complexity of variable elimination is $O(n \cdot k^{w+1})$ where:

- $n$ = number of variables

- $k$ = maximum cardinality (states per variable)

- $w$ = induced tree width (maximum factor size during elimination)

Critical insight: The elimination order dramatically affects performance. Finding the optimal order is NP-hard, but heuristics work well in practice:

- Min-neighbors: Eliminate variables with fewest dependent variables

- Min-weight: Minimize product of cardinalities of dependent variables

- Min-fill: Minimize edges added to the graph during elimination

# Using different elimination orders

# Min-fill heuristic (default in pgmpy)

inference_minfill = VariableElimination(model)

result1 = inference_minfill.query(['Cancer'], evidence={'XRay': 1})

# You can also specify custom elimination order

# For small networks, order matters less; for large ones, it's crucialJunction Tree Algorithm

The junction tree algorithm is the most sophisticated exact inference method. It’s particularly efficient when multiple queries need to be answered on the same network, as it preprocesses the network into a structure that enables fast repeated inference.

Core Concepts

The junction tree algorithm transforms the Bayesian network into a tree of cliques (fully connected subgraphs) that satisfies the running intersection property: if a variable appears in two cliques, it must appear in all cliques on the path between them.

Key advantages over variable elimination:

- Reusable structure: Process once, query many times efficiently

- Bidirectional message passing: Information flows in both directions

- Systematic approach: Well-defined compilation steps

Algorithm Steps

- Moralization: Convert directed graph to undirected by “marrying” parents of common children

- Triangulation: Add edges to eliminate cycles of length ≥4 without chords

- Clique Formation: Identify maximal cliques in the triangulated graph

- Junction Tree Construction: Build tree structure from cliques

- Message Passing: Propagate probabilities through the tree

Practical Implementation

from pgmpy.models import DiscreteBayesianNetwork

from pgmpy.factors.discrete import TabularCPD

from pgmpy.inference import BeliefPropagation

# Using the Asia network - a classic medical diagnosis example

from pgmpy.utils import get_example_model

# Load pre-built Asia network

# Variables: Visit to Asia, Tuberculosis, Smoking, Lung Cancer,

# Bronchitis, Either (TB or Cancer), X-ray, Dyspnea

asia_model = get_example_model('asia')

# Create belief propagation inference object (junction tree-based)

bp_inference = BeliefPropagation(asia_model)

# Calibrate the junction tree (preprocessing step)

# This builds the junction tree structure

bp_inference.calibrate()

# Now we can make multiple queries efficiently

# Query 1: Probability of lung cancer given smoking

result1 = bp_inference.query(

variables=['lung'],

evidence={'smoke': 'yes'}

)

print("P(Lung Cancer | Smoking):")

print(result1)

# Query 2: Probability of tuberculosis given X-ray abnormality

result2 = bp_inference.query(

variables=['tub'],

evidence={'xray': 'abnormal'}

)

print("\nP(Tuberculosis | Abnormal X-ray):")

print(result2)

# Query 3: Multiple variables simultaneously

result3 = bp_inference.query(

variables=['lung', 'bronc'],

evidence={'smoke': 'yes', 'dysp': 'yes'}

)

print("\nP(Lung Cancer, Bronchitis | Smoking, Dyspnea):")

print(result3)When to Use Junction Tree vs Variable Elimination

Use Variable Elimination when:

- Making single or few queries on the network

- Network structure changes frequently

- Memory is constrained (junction tree can be memory-intensive)

Use Junction Tree when:

- Making many repeated queries

- Network structure is fixed

- Need to update evidence multiple times

- Real-time inference requirements after preprocessing

Real-World Application: Disease Diagnosis

Let’s build a complete medical diagnosis system that demonstrates exact inference in a realistic scenario:

import pandas as pd

from pgmpy.models import DiscreteBayesianNetwork

from pgmpy.factors.discrete import TabularCPD

from pgmpy.inference import VariableElimination

# Create a multi-symptom disease diagnosis network

# Structure: Risk factors -> Diseases -> Symptoms

model = DiscreteBayesianNetwork([

# Risk factors

('Age', 'HeartDisease'),

('Smoking', 'HeartDisease'),

('Smoking', 'LungCancer'),

# Diseases

('HeartDisease', 'ChestPain'),

('HeartDisease', 'Fatigue'),

('LungCancer', 'ChestPain'),

('LungCancer', 'Cough'),

])

# Define CPDs with evidence-based probabilities

# P(Age) - 0: <50, 1: 50-70, 2: >70

cpd_age = TabularCPD('Age', 3, [[0.4], [0.4], [0.2]])

# P(Smoking) - 0: never, 1: former, 2: current

cpd_smoking = TabularCPD('Smoking', 3, [[0.6], [0.25], [0.15]])

# P(HeartDisease | Age, Smoking) - simplified for clarity

cpd_heart = TabularCPD(

'HeartDisease', 2,

# Rows: No HD, Has HD

# Columns vary by Age (3) x Smoking (3) = 9 combinations

[[0.95, 0.90, 0.85, 0.90, 0.80, 0.70, 0.85, 0.70, 0.50],

[0.05, 0.10, 0.15, 0.10, 0.20, 0.30, 0.15, 0.30, 0.50]],

evidence=['Age', 'Smoking'],

evidence_card=[3, 3]

)

# P(LungCancer | Smoking)

cpd_lung = TabularCPD(

'LungCancer', 2,

[[0.99, 0.90, 0.70], # No cancer

[0.01, 0.10, 0.30]], # Has cancer

evidence=['Smoking'],

evidence_card=[3]

)

# P(ChestPain | HeartDisease, LungCancer)

cpd_chest = TabularCPD(

'ChestPain', 2,

[[0.95, 0.70, 0.80, 0.40], # No pain

[0.05, 0.30, 0.20, 0.60]], # Has pain

evidence=['HeartDisease', 'LungCancer'],

evidence_card=[2, 2]

)

# P(Fatigue | HeartDisease)

cpd_fatigue = TabularCPD(

'Fatigue', 2,

[[0.90, 0.30], # No fatigue

[0.10, 0.70]], # Has fatigue

evidence=['HeartDisease'],

evidence_card=[2]

)

# P(Cough | LungCancer)

cpd_cough = TabularCPD(

'Cough', 2,

[[0.95, 0.20], # No cough

[0.05, 0.80]], # Has cough

evidence=['LungCancer'],

evidence_card=[2]

)

# Add all CPDs

model.add_cpds(cpd_age, cpd_smoking, cpd_heart, cpd_lung,

cpd_chest, cpd_fatigue, cpd_cough)

# Verify model

assert model.check_model()

# Perform diagnostic inference

inference = VariableElimination(model)

# Scenario 1: 65-year-old current smoker with chest pain and cough

evidence1 = {

'Age': 1, # 50-70 years

'Smoking': 2, # Current smoker

'ChestPain': 1, # Has chest pain

'Cough': 1 # Has cough

}

result_heart1 = inference.query(['HeartDisease'], evidence=evidence1)

result_lung1 = inference.query(['LungCancer'], evidence=evidence1)

print("Scenario 1: 65yo smoker with chest pain and cough")

print(f"P(Heart Disease): {result_heart1.values[1]:.3f}")

print(f"P(Lung Cancer): {result_lung1.values[1]:.3f}")

# Scenario 2: 35-year-old non-smoker with fatigue only

evidence2 = {

'Age': 0, # <50 years

'Smoking': 0, # Never smoked

'Fatigue': 1 # Has fatigue

}

result_heart2 = inference.query(['HeartDisease'], evidence=evidence2)

print("\nScenario 2: 35yo non-smoker with fatigue")

print(f"P(Heart Disease): {result_heart2.values[1]:.3f}")

# Scenario 3: What if we add more evidence?

evidence3 = {

'Age': 2, # >70 years

'Smoking': 1, # Former smoker

'ChestPain': 1,

'Fatigue': 1,

'Cough': 0 # No cough

}

result_heart3 = inference.query(['HeartDisease'], evidence=evidence3)

result_lung3 = inference.query(['LungCancer'], evidence=evidence3)

print("\nScenario 3: 75yo former smoker, chest pain, fatigue, no cough")

print(f"P(Heart Disease): {result_heart3.values[1]:.3f}")

print(f"P(Lung Cancer): {result_lung3.values[1]:.3f}")This example demonstrates how exact inference enables:

- Diagnostic reasoning: From symptoms to likely diseases

- Predictive reasoning: From risk factors to probable outcomes

- Evidence combination: How multiple symptoms update beliefs

Common Pitfalls and Troubleshooting

1. Computational Intractability

Problem: Inference takes too long or runs out of memory.

Diagnosis: Check the induced tree width. Networks with tree width >15-20 often become intractable.

# Check tree width approximation

from pgmpy.base import DAG

dag = DAG(model.edges())

# Approximate tree width (exact computation is NP-hard)

# Rule of thumb: if elimination creates factors with >10-15 variables,

# consider approximate inferenceSolutions:

- Simplify the network structure (reduce connections)

- Use approximate inference methods (MCMC, variational inference)

- Apply cutset conditioning for specific network topologies

- Consider parallelization for independent subnetworks

2. Numerical Underflow

Problem: Probabilities become too small, resulting in zero values.

# Bad practice - direct multiplication leads to underflow

prob = 0.001 * 0.001 * 0.001 # Becomes effectively zero

# Good practice - use log probabilities

import numpy as np

log_prob = np.log(0.001) + np.log(0.001) + np.log(0.001)

prob = np.exp(log_prob) # Convert back when neededSolution: pgmpy handles this internally, but be aware when implementing custom algorithms.

3. Invalid Network Structure

Problem: Model fails validation with cryptic errors.

# This will fail - violates DAG property (cycle)

bad_model = DiscreteBayesianNetwork([

('A', 'B'),

('B', 'C'),

('C', 'A') # Creates cycle!

])Solution: Ensure your network is a proper DAG with no cycles. Use model.check_model() frequently during development.

4. Evidence Conflicts

Problem: Setting impossible evidence values (zero probability in all worlds).

# This might create impossible evidence

result = inference.query(

['Disease'],

evidence={'Symptom1': 1, 'Symptom2': 1}

)

# If CPDs make this impossible, inference failsSolution: Check if evidence is possible given the CPDs. Use model.simulate(n_samples=100) to understand plausible evidence combinations.

5. Incorrect CPD Dimensions

Problem: CPD dimensions don’t match network structure.

# Wrong - CPD has wrong evidence cardinality

cpd_wrong = TabularCPD(

'Child', 2,

[[0.9, 0.1], # Only 2 columns but parent has 3 states!

[0.1, 0.9]],

evidence=['Parent'],

evidence_card=[3] # Says parent has 3 states

)Solution: Ensure CPD column count equals product of evidence cardinalities. For 2 binary parents: need $2 \times 2 = 4$ columns.

Performance Optimization Tips

1. Preprocessing for Multiple Queries

# Inefficient - creates new inference object each time

for query in queries:

inference = VariableElimination(model)

result = inference.query(query)

# Efficient - reuse inference object

inference = VariableElimination(model)

for query in queries:

result = inference.query(query)2. Evidence Batching

# When making similar queries with different evidence

evidence_list = [

{'Symptom1': 1, 'Symptom2': 0},

{'Symptom1': 0, 'Symptom2': 1},

{'Symptom1': 1, 'Symptom2': 1}

]

results = []

for evidence in evidence_list:

result = inference.query(['Disease'], evidence=evidence)

results.append(result)3. Choosing the Right Inference Algorithm

from pgmpy.inference import (

VariableElimination, # General purpose, single queries

BeliefPropagation, # Multiple queries, junction tree

)

# For single queries on large networks

ve_inference = VariableElimination(model)

# For multiple queries on same network

bp_inference = BeliefPropagation(model)

bp_inference.calibrate() # One-time preprocessingWhen to Use Approximate Inference Instead

Exact inference isn’t always the answer. Switch to approximate methods when:

- Tree Width >20: Networks become computationally intractable

- Real-time Requirements: Need sub-second responses with large networks

- Continuous Variables: Many continuous nodes without Gaussian assumptions

- Temporal/Sequential Models: Long-horizon dynamic Bayesian networks

- Online Learning: Model parameters update frequently

Approximate alternatives:

- MCMC Sampling: Gibbs sampling, Metropolis-Hastings

- Variational Inference: Mean-field approximation

- Loopy Belief Propagation: For networks with cycles

- Particle Filtering: For dynamic Bayesian networks

# Example: Switching to approximate inference

from pgmpy.sampling import GibbsSampling

# When exact inference is too slow

approx_inference = GibbsSampling(model)

samples = approx_inference.sample(

size=10000, # More samples = better approximation

evidence={'Symptom': 1}

)

# Estimate probabilities from samples

prob_disease = samples['Disease'].mean()Conclusion

Exact inference in Bayesian networks provides mathematically precise probabilistic reasoning for complex decision-making under uncertainty. We’ve explored the two primary algorithms:

Variable Elimination offers simplicity and efficiency for single queries, with performance heavily dependent on elimination ordering. It’s the workhorse algorithm for most practical applications.

Junction Tree provides a more sophisticated framework ideal for multiple queries on the same network, preprocessing the structure once for efficient repeated inference.

The key to successful exact inference is understanding when it’s tractable. Networks with favorable structure (low tree width, sparse connections) allow exact inference to shine. For complex networks, be prepared to transition to approximate methods or simplify your model.

Next steps to deepen your understanding:

- Implement custom elimination orderings and compare performance

- Explore mixed networks with both discrete and continuous variables

- Study dynamic Bayesian networks for temporal reasoning

- Experiment with real-world datasets using the bnlearn repository

- Benchmark exact vs. approximate inference on your specific problems

The field continues to evolve with GPU-accelerated inference, neural-symbolic integration, and causal discovery methods. Mastering exact inference provides the foundation for these advanced topics.

References:

-

GeeksforGeeks - Exact Inference in Bayesian Networks - https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/artificial-intelligence/exact-inference-in-bayesian-networks/ - Comprehensive overview of exact inference methods and their mathematical foundations (July 2025)

-

Bayesian Networks Tutorial (Ermon Group, Stanford CS228) - https://ermongroup.github.io/cs228-notes/inference/ve/ - Detailed explanation of variable elimination algorithm with complexity analysis

-

pgmpy Documentation - Discrete Bayesian Networks - https://pgmpy.org/models/bayesiannetwork.html - Official API documentation for pgmpy implementation (2025)

-

Wikipedia - Junction Tree Algorithm - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Junction_tree_algorithm - Mathematical description of junction tree construction and message passing (December 2025)

-

Ankur Ankan & Johannes Textor (2024) - pgmpy: A Python Toolkit for Bayesian Networks, JMLR 25(265):1-8 - Primary reference for pgmpy library features and algorithms

-

David Heckerman - A Tutorial on Learning With Bayesian Networks - https://arxiv.org/pdf/2002.00269 - Classic tutorial covering inference algorithms and their applications